Executive Condominiums (ECs) are one of the most popular private, or shall I say semi-private housing options in Singapore. Despite their initial HDB-like restrictions, ECs have been a successful housing scheme reaching all the way back to the ‘90s, surpassing other shorter-lived initiatives like DBSS. Today, I’m going to cover the main differences and expectations regarding ECs, versus a “fully private” condo.

Key differences between ECs and Private Condos

The EC scheme was introduced in 1997, although at the time it was called the Executive Condominium Housing Scheme (ECHS). Ever since its inception, ECs have been designed as a form of housing for “sandwiched” Singaporeans:

ECs are for those who earn more than the income ceiling for HDB flats, but still can’t comfortably afford a fully private condo. As of June 2024, the income ceiling for a couple to purchase a HDB flat with an HDB loan is $14,000, whereas the income ceiling for an EC is $16,000. There is no income ceiling to purchasing a fully private condo.

ECs, like private condos, are built and marketed by private developers. This means they have all the usual quality and facilities of a regular condo, such as pools, gyms, and so forth.

However, ECs are considered HDB properties, and are subject to HDB rules, for their first 10 years. After this, an EC becomes privatised, and are treated as if they are any other condo.

In addition, an EC has a five-year MOP, which is only applicable to the first batch of buyers.

For example, The Vales at Anchorvale Crescent was built in 2017.

Right up till 2023, The Vales would have been subject to the five-year MOP. That is, the owners would have been unable to sell the unit on the open market, or to rent out the entire unit (renting out individual rooms would still have been allowed). This is exactly the same as the MOP restrictions on an HDB flat.

Starting from 2023, the owners can rent out their whole unit, and freely sell the condo on the open market. However, they still cannot sell to people who don’t meet HDB eligibility requirements, such as foreigners.

Starting from around 2028, The Vales would be fully privatised. At that point, The Values no longer counts as an HDB property. It can be sold to foreigners and companies alike, which also makes it eligible for en-bloc sales to private developers.

Here’s a quick summary:

| EC | Private Condo | |

| Citizenship status | For the first 10 years, must meet the usual HDB eligibility criteria. This means only Singapore citizens or PRs can buy. After the 10th year, HDB eligibility no longer applies. | You can sell to anyone, including foreigners and corporate entities. |

| Income ceiling | $16,000 per month, but there is no income ceiling after privatisation | No income ceiling. |

| Financing restrictions | Buyers must meet both the Mortgage Servicing Ratio (MSR) and Total Debt Servicing Ratio (TDSR). | Buyers only need to meet the TDSR. |

| Minimum Occupancy Period (MOP) | Five-year MOP, for the first batch of buyers. Subsequent buyers are not restricted by MOP. | Does not apply to private housing. |

| Additional Buyers Stamp Duty (ABSD) | There’s no need to pay ABSD if you are upgrading to an EC from your flat. | If you buy the new unit before selling your previous home, you need to pay the ABSD within 14 days of the transaction (but you can apply for ABSD remission later, if you qualify) |

| Housing grants | Housing grant of up to $30,000, based on usual HDB eligibility criteria. There are no housing grants for already privatised ECs. | Does not apply to private housing. |

| Lease status | 99-year leasehold only. | Can be 99-year leasehold, or 999-years / freehold. |

| Pricing | Roughly 20% to 30% less than a private counterpart. | Always priced higher than an EC. |

The most important points to focus on

I would highlight these key points to look at, if you’re deciding between the two:

- Passing the MSR

- Avoiding ABSD complications for upgraders

- The importance of the five-year mark

- Qualitative differences

1. Passing the MSR

The MSR is a financing restriction that only applies to HDB properties. Under the MSR, the monthly loan repayment cannot exceed 30% of your monthly income.

For example, if the monthly loan repayment amount is $3,500*, then the minimum combined income of the borrowers must be $11,667 per month.

If you exceed the MSR, you may have to make a bigger down payment on the EC, or stretch out the loan tenure. Note that the MSR only applies to HDB properties, so there’s no need to worry about it if you’re buying a private condo, or an EC that has already been privatised.

Besides the MSR, there is the TDSR which applies to all bank loans. The TDSR limits the monthly loan repayment to 55% of your monthly income, inclusive of other debts such as car loans, student loans, etc. (This is different from the MSR, which only cares about the home loan, not your other debts).

*A floor interest rate of at least 4% is used to calculate your MSR and TDSR, regardless of whether your actual home loan rate is lower.

Do consider that the MSR is a natural price restriction on an EC.

An EC has an income ceiling of $16,000, so the absolute maximum loan repayment, under the MSR, is $4,800.

This places a natural hindrance on the ECs price growth. Because until it’s fully privatised, buyers who would bust the MSR cap need to borrow less (i.e., they have a higher initial cash outlay).

For example, a couple below 35 years old with a combined income of $16,000 would be able to borrow $1 million for the EC purchase. If they are looking at 75% financing, the EC would be priced at about $1.33 million. However, in today’s new EC projects, a typical 3-bedroom of about 1,000 sq ft would be around $1.5 million. The couple would have to fork out more cash / CPF.

2. Avoiding ABSD complications for upgraders

If you upgrade from a flat to a condo, you can opt to buy your new condo before selling your flat (this can mitigate the need for temporary rental, as you can wait till the condo is built before you move out and sell the flat).

However, there is a cost to this convenience.

If buying a private condo, you are still required to pay the ABSD, within 14 days of buying the condo. This is 20% of the condo price, for Singapore citizens.

You can then apply for ABSD remission later if (1) you are a married couple with one of you being a Singapore citizen, and (2) you sell your flat within six months of buying the new condo. Failure to do so means losing the ABSD money.

This can trap some buyers between a rock and a hard place, as they’re forced to choose between a higher cash outlay, or having to make expensive rental arrangements.

Plus, I might add, it’s quite stressful to worry about selling your flat within the six-month time limit.

With a non-privatised EC however, there’s no need to pay the ABSD if you’re just upgrading from your flat. This is no small convenience for home owners, especially for families where moving twice could be disruptive (e.g., to your children’s school routines).

3. The importance of the five-year mark

Some buyers aim to purchase a resale EC, as there’s no MOP. This makes it possible, for instance, to live with the in-laws while immediately renting out your whole EC unit.

On the flip side, some owners aim to purchase ECs at the earliest stages, when they are cheapest. They then seek to sell the EC and upgrade to a private condo, as soon as the five-year mark is reached. This is such a common practice that I have written about it in the article “Are ECs an assured way to make money?” .

For example, here’s a look at The Vales, which has just seen its first sales after reaching MOP:

(Note: there are occasionally sales that happen before the MOP. These are special circumstances where buyers are allowed to sell earlier, due to situations such as divorce, the passing of a co-borrower, etc.)

According to Square Foot Research, The Vales averaged $789 psf during initial sales in 2015, and has been selling for around $1,493 psf as of June 2024.

Another example is Westwood Residences, which also recently reached its MOP in 2023:

Initial prices stood at $803 psf in 2015, but recently sales have reached $1,297 psf.

As you can see, these rather big price jumps at the five-year mark make ECs quite ideal for property progression strategies. For buyers who can afford a head start, it might make sense to start off buying an EC instead of a BTO flat.

The price gap between an EC and a private condo is likely to be narrower than that of a resale flat and a condo (see below).

4. Qualitative differences

To be very frank, most ECs are not in prime locations. In fact, ECs have a reputation for being quite far from MRT stations (with some exceptions), and almost always appear in non-mature neighbourhoods.

This has improved in recent years, with some ECs like Parc Canberra, 1 Canberra, and Tampines Trilliant being within walking distance to train stations. But as a whole, most ECs are less conveniently located than their private counterparts.

(They’re less conveniently located than most HDB counterparts too)

There is also the subjective, but pervasive, belief that ECs are of lower quality. Till today, there are buyers who insist that ECs are more cramped, have smaller facilities, etc. The reason given is the lower costing that developers are forced to work with.

This is not something that can be conclusively “proven,” as it depends on personal taste and the specific project. But with the emergence of “luxury ECs” like Ola, which just reached TOP in 2023, I would opine that – if it was true before – it’s not so today.

Developers do have to sell the ECs they build, and their names are attached to the projects; most wouldn’t risk delivering a bad product.

The big question: Do ECs outperform private condos?

I won’t dwell too much on this here, as I have covered it in “Are ECs an assured way to make money?”.

Instead, I’ll let this speak for itself:

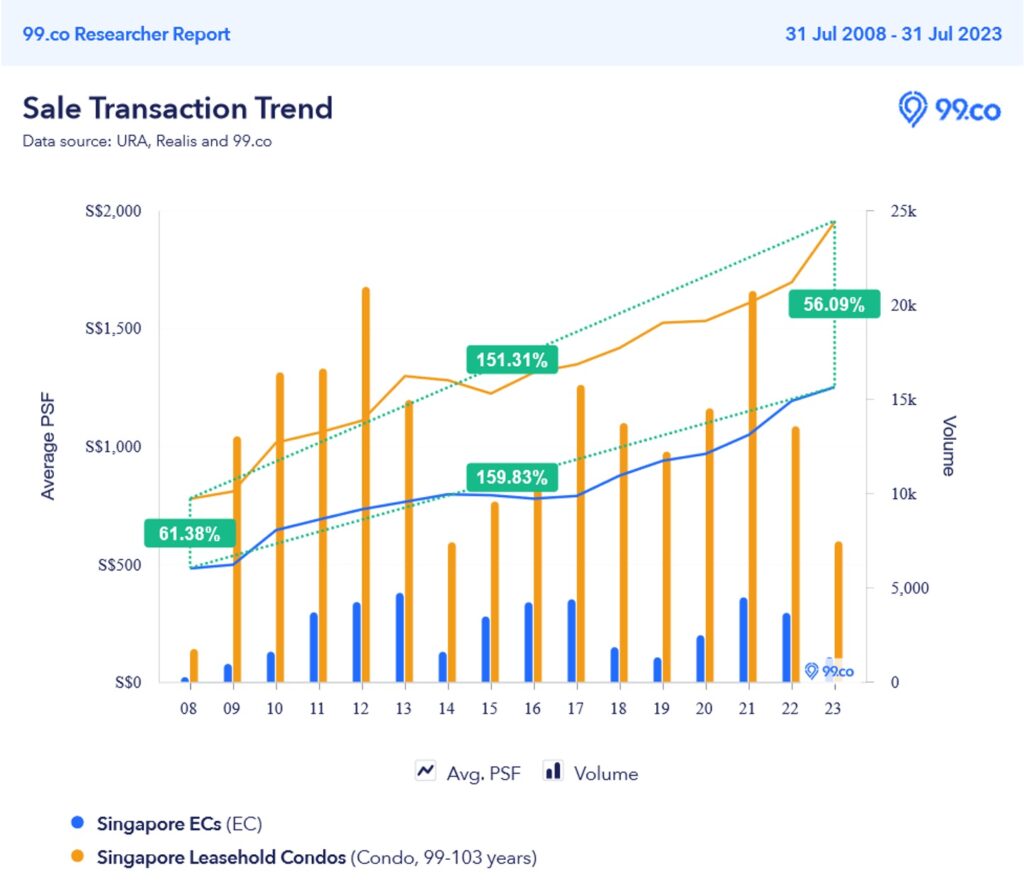

Here, I’ve compared EC price movements islandwide, with leasehold private condos (it isn’t fair to include freehold, as all ECs are leasehold).

Over a 15-year period, ECs have appreciated better than their private counterparts. They’ve risen from an average of $481 to $1,250 psf, an increase of about 159.8%.

Private leasehold condos have risen from $776 to $1,951 psf in the same period, an increase of about 151.3%.

Note that the price gap between ECs and private counterparts has narrowed: there was a price difference of 61.3% between them in 2008, but the gap has since narrowed to 56%.

The reason comes down to the lower price point of ECs, which gives them significantly more room to appreciate.

You can also consider that ECs have got a grant of up to $30,000. I know this is not a huge amount, but it helps to further subsidise the price for buyers, in addition to the lower initial cost.

All in, ECs are a good way to progress toward private home ownership. If it’s within your budget, it can provide a better head start than an HDB flat. But if you can already afford a private property, you may find the HDB-like restrictions chafing; and you may want to look at a resale EC that’s either privatised or at least past its MOP.

For more personalised help, reach out to me, and I can help you work out if an EC is really the best choice for you right now.