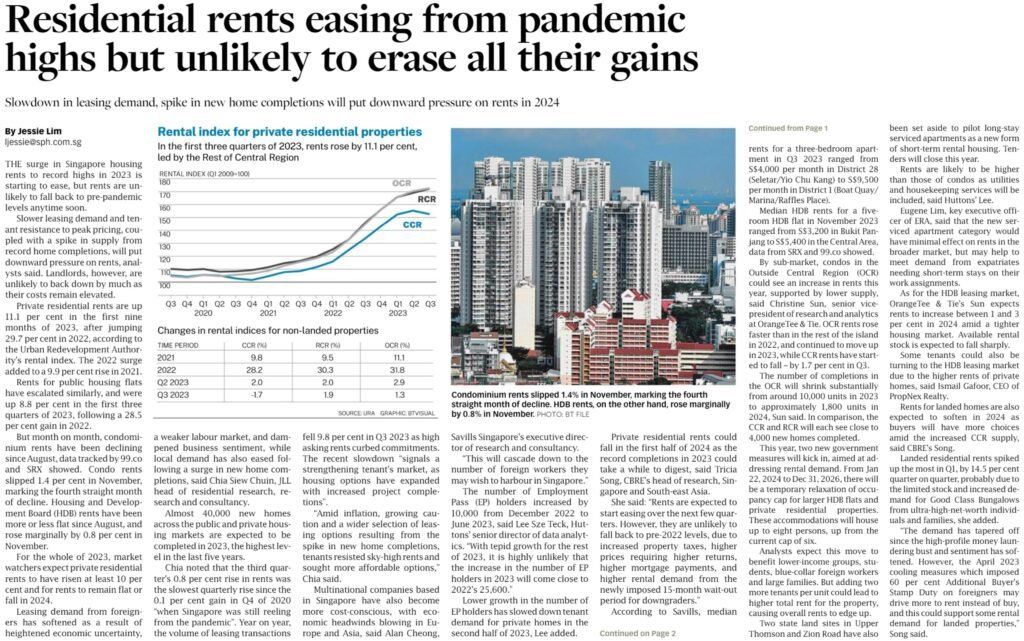

In the past few years, the Singapore rental market has hit record heights. In a Business Times report on 8 January 2024, for instance, it was reported that rental rates grew year-on-year by 9.9%, 29.7% and 11.1% for 2021, 2022 and the first nine months of 2023. The surge in the Singapore housing rents to record highs in 2023 led many people to start dreaming of how rich they could be, if only they were landlords. Then, the concept of co-living, which was rather unheard of before the pandemic, appeared on the horizon. There are even seminar gurus (I shall not name their names, but you would probably have seen their ads on Facebook and Youtube claiming how their students are earning a fat passive income every month) conducting programmes that cost up to $10,000 per participant, just to teach the concept of co-living. They claim that even without owning property – they could be landlords and collect rent. But is that too good to be true?

What is co-living?

If you’ve heard of co-working spaces, the concepts share similarities; the difference is that co-living spaces are residential rather than offices. For the most part, a co-living space is a unit rented by unrelated tenants, who have their own rooms but share certain facilities.

Another broadly similar concept, if you had lived on-campus during your university days, is the campus dorm (the only difference is that a co-living space is fancier, and not everyone is a student). So instead of bumping into your hostel mates in the hostel toilets or pantry after a late night of mugging, co-living tenants would find themselves bumping into other tenants in the shared kitchen cooking maggi mee.

Depending on how it’s run, co-living spaces also have some variations. For example, some include cleaning services, and come with “free” wifi and utilities, almost like serviced apartments (with a higher monthly price tag, of course! Nothing is free). Some are very basic, and have little more than a shared pantry and living room TV set.replica watches,replica watches uk,fake watches.

But how can we own a co-living space without owning a property?

Simply put, this is done by sub-letting. The operator of the co-living space is the master tenant of the property, who pays rent to the landlord.

The landlord (who must authorise the co-living) only collects from this master tenant, not the sub-tenants. For example:

The landlord owns the property, and charges the master tenant $4,500 per month for a condo unit. The master tenant brands the unit as a co-living space, and rents it out to five or six other tenants, who collectively pay around $6,500 in rent.

(Well, that’s what the co-living operator hopes for – it’s dependent on their marketing skill to see how much they can convince the sub-tenants to pay).

The co-living operator pockets the excess $2,000, deducts various costs like the utilities and cleaning, and whatever is left is their profit.

This way, the co-living operator doesn’t need to put down capital to buy the property, but is still making money off tenants; or rather sub-tenants.

So why doesn’t everyone rush out to do this?

There are some key risks that may not be immediately obvious, and these include:

- Volatility in the Singapore rental market

- Correction of Singapore’s housing shortfall by the authorities

- A rising interest rate environment

- Being at the mercy of the landlord

- Hazards of dealing with multiple unrelated tenants

- An evolving regulatory environment

1. Volatility in the Singapore rental market

Rental rates in Singapore are subject to up-and-down periods. While times are good now, did you know that between 2013 to 2019, rental rates were in near-consecutive decline?

The rise between 2020 to the present has been unusually sharp; an increase of over 53.6 per cent. But keep in mind that 2020 was characterised by a black swan event called Covid-19.

Due to the shift to Work-From-Home jobs (and perhaps trauma from the Circuit Breaker event, when some households were too small for the whole family to be there 24/7), there was an explosion in demand for new homes.

This caused higher housing demands, and we also saw a surge in rental. This was caused by:

- Singaporeans who were driven to buy their own property, and were renting while they wait for their new home to be completed (let’s not forget there were many HDB owners who followed the “asset progression” model, sold their HDB and bought a new project as their next home).

- Singaporeans who needed their own space, but couldn’t afford to buy private property or weren’t eligible for HDB flats, and so turned to renting (especially true for young working professionals who were still staying with their parents, but needed more space besides their bedrooms now that they were working from home).

- Foreigners who were at one point stuck in Singapore and forced to rent, such as some Malaysian workers who couldn’t return home due to Movement Control Orders.

- The dearth of new rental supply as many new projects were still under construction due to the pandemic, and the tightness in the housing supply caused some existing landlords to hold back as they might have also needed the accommodation for themselves in case they made any property adjustments.

However, events like Covid-19 are not common. They are rare, probably once-in-a- decade situations, which may not be seen again for a good number of years. It’s not reasonable to count on it happening again soon. And definitely not reasonable to assume that rents will continue to remain high. In fact, rents have declined for 5 consecutive months from August to December 2023, wiping out the growth seen in the first half of 2023, as reported in the Business Times on 19 January 2024.

2. Correction of Singapore’s housing shortfall by the authorities

HDB has significantly ramped up production to make up for the shortfall. Even as I’m writing this, HDB has announced 100 BTO projects under construction, and 150 concurrent BTO projects by 2025.

In the private segment, the supply of new sites via the Government Land Sales programme has risen. We are expecting enough land for 9,250 units for 2023, which is the highest in around 10 years. We are also seeing a slew of completed projects hit the market, with some truly sizeable ones.

All these new projects have obtained TOP in 2023 – Normanton Park (1,862 units), Treasure at Tampines (2,203 units, the largest in Singapore), Parc Clematis (1,468 units), Riverfront Residences (1,472 units), Florence Residences (1,410 units) and Avenue South Residences (1,074 units).

With so many large projects reaching completion, there’s likely to be less demand from local tenants, who are going to wind up their leases and move into their completed homes.

At the same time, tenants have more choices now.

Even for foreign tenants – who make up the bulk of renters here – the completion of these large developments can mean heightened competition between landlords, and no shortage of options.

Economics 101 – more supply, (potentially) less demand means a downward pressure on price.

3. A rising interest rate environment

For now, co-living operators may still be profitable after paying the landlord. However, we are in an environment of rising interest rates.

Before Covid-19, a home loan rate of around 1% was still the norm. This was because the US Federal Reserve artificially forced down interest rates, to stimulate economic recovery from the pandemic. This had the knock-on effect of lowering mortgage rates in Singapore.

However, now that the pandemic is over, what we are witnessing is the wrath of the Fed having reversed course. Multiple interest rate hikes have driven home loan rates to peak at around 4.5% in Singapore in 2023.

To give you a sense of the difference: a 25-year loan for $1 million, at the old rate of 1% per annum, would have monthly repayments of roughly $3,800 per month.

Raise it to today’s average of 3%, and the monthly repayment goes up to around $4,700 per month.

Co-living operators who negotiated the rent in earlier years may be profitable for now, because their Tenancy Agreement (TA) was signed when interest rates were lower.

But when it’s time to renew their lease in 2024, 2025, or beyond, it’s likely that landlords will push for much higher rents, to compensate for the rising interest. So when you hear of co-living operators flex about their margins, keep in mind this may not be a lasting success.

And if you’re only just getting into the co-living industry today, you can expect that landlords have already factored in the rising rates. I wouldn’t count on getting the same low rates that earlier investors nabbed in 2020 or 2021.

4. Being at the mercy of the landlord

Unless you are the actual owner of the property, the spectre of the landlord will always be haunting you. Even without interest rates rising, it’s improbable that the landlord doesn’t know how much you’re making.

Not only can they push for higher rental rates, they can decide at any time they are going to take back the property and just operate the space by themselves. Landlords are just as capable of marketing their properties to multiple tenants.

If they do that, you need to consider what happens to your co-living assets. All the money you spent on branding, and sometimes the money you’ve spent on renovations, are all wasted.

I know of at least one co-living company who, as a condition of getting a longer lease, agreed to pay half the renovation costs of a condo unit for the landlord. When the lease expires, all of it goes to the landlord. You need to consider the consequences if you pay for such expenses, and are then later unable to carry on operating the space.

5. Hazards of dealing with multiple unrelated tenants

Some savvy readers would already be asking why, if the co-living is so profitable, the landlords don’t just operate it themselves rather than have a master tenant.

One answer is that many experienced landlords loathe dealing with multiple unrelated tenants. If you have six tenants rather than one master tenant, it means having to chase six different people for rental payments, and deal with complaints from six different people.

It also takes a lot of administrative effort: six different leases, with different dates and rental rates, is more of a headache than just handling one lease with a master tenant.

The other answer is that tenants often have a lot of conflicts with each other. Some are petty (e.g., complaints that one person showers too late and wakes them up), and some are serious (e.g., one tenant complains that another stole money from their room).

Furthermore, when you sign a tenancy agreement with the landlord as the master tenant, you usually take up a 3-year lease. It is not possible to have your sub-tenant taking up the same duration of such a long lease. These sub-tenants are likely to take up a lease of 3 months to 1 year, and they are extreme mobile. You will need to deal with pockets of down time as you find replacement sub-tenants.

And if a sub-tenant should default on payments to you, remember your landlord doesn’t care: you still need to pay them the rent on time.

As a co-living operator, you are the one that must deal with all this, while the landlord just sits back and collects from you. Do think hard about whether it’s worth the margins.

6. An evolving regulatory environment

Co-living is relatively new on the scene, and many of the regulations around it are still evolving. This can leave some important questions a little difficult to answer.

What happens if, for instance, a property goes en-bloc, while you’re operating a co-living space there? It’s uncertain how this will be worked out between you and your landlord, or you and the subtenants; but I suspect no one will be particularly happy.

You also need to consider that landlords can run into their own problems. What happens, for instance, if a landlord can’t pay the mortgage, and the bank moves to foreclose, while you’re subletting? This can involve a lot of expensive legal consultations, and messy negotiations.

Singapore is also quite strict when it comes to housing. We do not, for instance, allow Airbnb as a form of short-term rental. We don’t know for sure if, in the future, the government will also place added restrictions on co-living.

This is not to say co-living is guaranteed to go wrong

It may work out for some, and there are certainly some success stories. However, don’t be misled by assertions that it’s easy, or that the risks involved are low.

And while I’m aware that commercial property is not the same as residential property, the co-living trend has haunting echoes of the co-working trend. Remember co-working operator WeWork, which was big in 2010?

They rented offices and then sublet those offices, a strategy that’s disturbingly similar to some co-living companies today; and WeWork crashed due to its unsustainable business model.