I often encounter the opinion that freehold properties are superior; so much so that some buyers will refuse to consider any 99-year leasehold projects. In reality though, whether a property appreciates well – and its inherent comfort as a home – are dependent on many more factors besides its tenure. In fact, the traits of freehold projects are often the subject of the most exaggerated rumours, or serious misunderstandings. If you have a serious preference for freehold properties, I have come up with 5 myths that you should be aware of that may just make you think again.

Myth #1: Freehold projects always appreciate better over time

In theory, freehold projects should always beat leasehold projects over long periods. This is for reasons of lease decay, and we jump to this conclusion because it intuitively seems right.

Here’s the reality.

Above is the price appreciation of freehold condos from 1st quarter 2008 to 1st quarter 2024. Over a 16-year period, average freehold condo prices have risen from $926 psf to $1,806 psf, an increase of 95.03%.

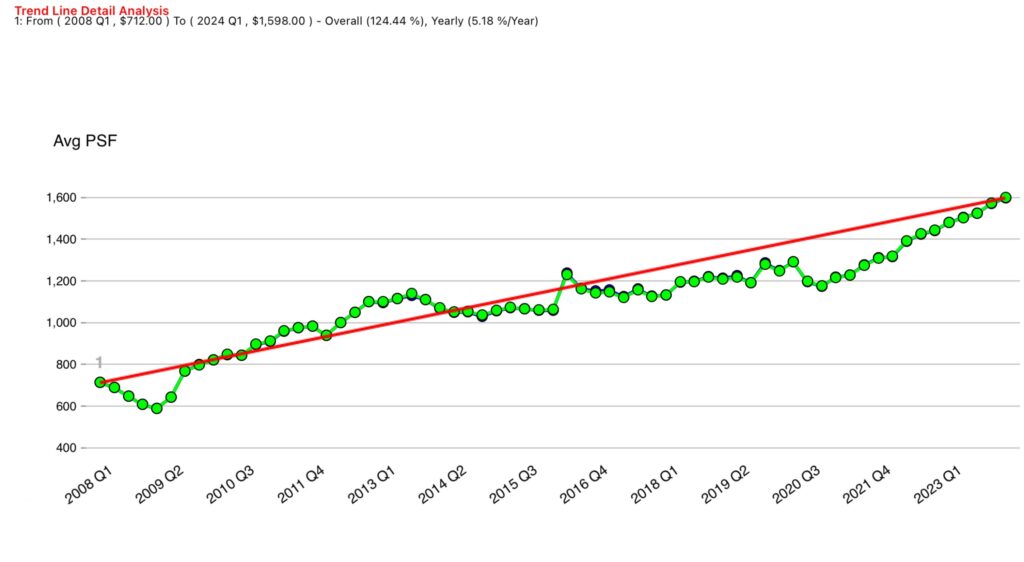

Above is the price appreciation of leasehold condos from 1st quarter 2008 to 1st quarter 2024. Over a 16-year period, average freehold condo prices have risen from $712 psf to $1,598 psf, an increase of 124.44%.

I have excluded Executive Condominiums (ECs) to avoid distortions, and I have grouped 999-year lease condos with freehold (as they are effectively similar). This is a Singapore-wide comparison.

Freehold condos have, on the whole, underperformed their leasehold counterparts. Note that the price gap between leasehold and freehold was about 30% back in 2008, but this has narrowed to just 13% in 2024.

How can this have happened?

The simple answer is that lease-status cannot account for most of a project’s appreciation. Factors such as location, timing of the purchase and sale, facilities, and layouts all have a much bigger impact on the property than its lease status.

Important:

My point here is not that the inverse is true (i.e., I am not saying leasehold will always beat freehold, as that’s an equally invalid myth).

The point is just that the lease status does not contribute as much to a condo’s performance as we like to imagine.

If we look at the above chart again, we realise that while leasehold properties (124.44%) appreciate more than freehold properties (95.03%) between 1st quarter 2008 to 1st quarter 2024, the gradient of both lines are almost the same. Simply put, this means both freehold and leasehold properties actually appreciate by the same $psf ($880 psf vs $886 psf) in absolute amount (as define by the gradient), but because leasehold properties tend to be cheaper, as a result we start off from a lower capital base and the percentage increase will be larger due to the smaller price quantum.

For example, comparing a leasehold property that appreciates from $1 million to $1.5 million with a freehold property that appreciates from $2 million to $2.5 million, we see that both properties appreciated by $500,000. But the percentage increase for the leasehold property is 50% versus 25% for the freehold property.

Myth #2: Lease decay is always a disadvantage to investors

Lease decay is a double-edged sword. There are investors who have also made lease decay work to their advantage.

For example, say you’re considering buying a new launch, leasehold unit at Tembusu Grand, which averages $2,446 psf (according to transaction data on SRX, as of May 2024).

About 10 minutes away from Tembusu Grand is the older leasehold condo of Dunman View (completed in 2004). This project averages a price of $1,560 psf (on SRX as of May 2024), a 56.8% price difference!

Keep in mind that, being just around 10 minutes away on foot, the locational advantages of Dunman View may be quite similar.

Setting aside some resale costs (e.g., renovations are usually more costly for resale), this can represent significant savings for a buyer. And if you know you’re not staying in the area indefinitely – such as if you know you’ll sell within the next decade – it could make sense to save money by choosing the older project. You can even invest the savings elsewhere for returns.

I know that’s not what property agents will tell you. They will staunchly argue that buying a new launch is always better than buying a resale. While I do not wish to go into the details (probably I can leave that for another article), there are situations where a resale would be better than a new project.

Another example would be rental properties.

A freehold property is roughly around 20% more than its leasehold counterpart. However, this has no bearing on the rental income it generates (tenants will not pay more to rent a freehold unit; it’s of no difference to them whether your condo is leasehold or freehold).

Gross rental yield = (Annual rental income) / (Property price) x 100, so:

A $2 million freehold unit, with $48,000 a year in rental, is a rental yield of 2.4%.

The $1.6 million leasehold counterpart, with the same rental rate, has a yield of 3%.

Here, the leasehold status is actually working to the advantage of the landlord, due to the lower price of the asset.

This is not to say lease decay is negligible. Lease decay does have an impact on eventual resale value; but lease decay alone doesn’t mean leasehold properties will always underperform.

Myth #3: Freehold is better because it’s there “forever”

First, the government can take back freehold land if it’s needed usually for the construction of significant infrastructural projects. This happened in January 2011, for example, when a row of landed terrace houses facing Marymount MRT station along Marymount Road were compulsorily acquired by the government to facilitate the construction of the North-South expressway.

Second, we should consider how long a freehold condo really sticks around. Most condo projects, whether they are leasehold or freehold, do not make it past the age of 40*. Usually by that point, redevelopment (e.g., in the form of an en-bloc sale) is likely to happen as the maintenance cost is getting expensive.

I would invite you to consider the number of condos you know, that date back to before 1980. Barring a few rarities like Pandan Valley, Kimsia Court, or projects that are walk-ups or mainly commercial (e.g., International Plaza and Novena Court), such condos are very rare.

At some point, as the Gross Plot Ratio (GPR) of the land increases, and the value of the built-up amenities improves, the land is likely to become more valuable than the property sitting on it. This gives developers an opportunity to make an attempt at collective sale as the revenue generated from the potential sale of the redeveloped new project would be far greater than land acquisition and construction cost.

So if you have aspirations of your descendants all living in the same property, I should point out it’s more likely that an en-bloc will happen before your children or grand-children inherit the unit. (This is true for most condo, but may be a different story for a landed property).

Within this context, you may want to rethink whether there’s a big difference between leasehold and freehold properties.

*In case you’re wondering why 40, it’s likely because this is the age at which buyers start having problems with financing. When a property has 60 or fewer years on the lease, the bank may drop the maximum loan quantum to 55% instead of the usual 75%. This is up to the discretion of the bank in question, but this is certainly one area where leasehold properties are at a disadvantage.

Myth #4: Leasehold properties have worse en-bloc potential

This is a semi-truth.

When developers buy over leasehold properties, they will top up the lease back to 99-years. The cost of this top-up is based on the SLA Land Betterment Charge rates (they used to be called Development Charge and Differential Premium); but the more advanced the lease decay, the more the developers must pay to top it up.

This really does make freehold properties more attractive for an en-bloc, as the developer doesn’t need to pay for a top-up.

There’s also the issue of bargaining power. When a condo is extremely old, and the clock is ticking for the owners, developers have the upper hand. The longer you wait to accept the en-bloc, the more advanced the lease decay becomes.

Freehold property owners, on the other hand, have no time limit. They have no inclination to budge until they get the price they’re happy with.

So that part of it is true.

However, an en-bloc sale is dependent on many other variables. A freehold property may end up being harder to en-bloc, for instance, because of factors like:

- The size of the land plot (developers have only five years to complete and sell off the property, so they may not have the confidence to take on large projects).

- The willingness of the various owners (freehold owners are more often the ones seeking an inter-generational asset, so tend to be less accepting of an en-bloc).

- The current state of the property market.

- Amenities and location.

And much more. So while a freehold property does have more en-bloc potential and attractiveness, freehold status is not a guarantee of a successful en-bloc.

Myth #5: There’s just leasehold, and freehold / 999-year lease

There’s a third category.

Leasehold properties can be on freehold land, and this is a disadvantage to buyers.

Consider a property like Red House, with a tenure described as “Freehold, 99-years from 06/01/2012, 99-years leasehold”.

This is not a typo. It means that the land under the project is owned by some other entity, which can be anything from a company (perhaps another developer), to a private owner, to a government body.

What has happened here is that the land owner has leased out the land, to a developer to build a condo on it. When the condo’s lease expires, the original owner gets the land back. Hence, it’s a leasehold property on freehold land.

Some buyers assume that “leasehold” just means everything including the land is leasehold, and this can lead to a problem. If there’s an attempt at a collective sale later, a third party – the owner of the actual land – may have to be persuaded to allow the redevelopment. If they don’t like it, the en-bloc sale may be impossible.

In this regard, leasehold properties on freehold land can be considered disadvantaged, versus regular leasehold properties.

Ultimately, lease status should not be given excessive importance when shortlisting properties

If I had to equate property investment to a marathon, the lease status would be the equivalent of the runner’s shoes. Good shoes matter; but not so much that the shoes alone will cause you to win the race. (Well, a Kenyan professional athlete with a lousy pair of shoes will easily win an amateur runner wearing the best running shoes. You get the point? Shoes alone do not win you a race).

When shortlisting your property, it’s better to account for factors like location and overall quantum first. Freehold or leasehold status can then be one of the added factors that tilt you toward one project or another.

If you focus too much on lease status, and insist on only buying freehold (or vice versa), you might miss a lot of other key factors.

If you’re having trouble deciding, reach out to me and we can do a walkthrough. Some comparisons will help to determine if your freehold choices are worth the premium. Or would it be better to invest in a leasehold property?